1. Logical Glances

I dislike “left brain” film watching for three reasons.

The first reason is because it really isn’t how movies are meant to be absorbed. At all. Narratives are emotional experiences and as such, they are constructed to elicit just that. They are meant to make you feel things at the precise intended moment: scared, elated, adoring, or tickled with laughter, etc. And then they’re supposed to take those emotions and connect them to a deeper thematic point that actually means something to your life. But the thing about left-brain movie watching is that it looks at a film’s “construction” with the opposite intent: it tackles plotting in inane terms like “would have made more sense for the character to do” (which often ignores the idea that a character is not only supposed to make mistakes, it results in a more boring movie). It misunderstand the very function of drama. And thus it hilariously pursues the things that actually disconnect you from the emotional moment, all so the left-brain can check a box and tell you that something is logical. Which is why left-brain thinking gets people bent out of shape about plot holes (which often aren’t even plot-holes). So engaging in movies this way is, quite frankly, absurd. It would be akin to me looking at some math equations and asking, “but what does this quadratic formula make you feel?” And I guess it might be able to make you feel something, the same way you could go about analyzing a movie in a left brain way…

It’s just not the point.

Because of that, the second reason I dislike left-brain movie watching is because I don’t like the discussion that comes out of that mindset. Rather than gettin into the matter of interpretation, it becomes all about “answering” the “questions.” Interpretations therefore become “explanations,” and it creates a kind of black-and-white approach to trying to understand a storyteller’s logical intent over their emotional intent. Again, sometimes left-brain analysis is innocuous. If you wanna fall down the JJ Abram’s rabbit holes of easter eggs then go nuts and post on forums to your heart’s content. My problem is when that activity is not viewed as the fun “side thing” and instead is thought of as the purpose of the narrative. And that’s never the intent of a narrative (at least in like 98% of cases). Even much ballyhooed “hard sci-fi” writers like Phillip K. Dick were enormously emotional and dealt in heavy abstraction. So when we go down the rabbit hole of left-brain logic, we misunderstand what we’re really after. Especially with the Abram’s mystery box approach, because it is actually a con game of mystery with no real answer (which he’s made clear over and over and over again). So the real reason not to watch movies in a left brain way?

It’s because you will never, ever get what you actually want.

And the third and secretly-most-devastating reason I don’t like it, is because the left-brain narrative approach almost always ties into a lot of sexist crap. I’m not kidding. There’s a reason the tech industry deals with a lot of systemic sexism, especially when people just think they’re being logical (and obviously Hollywood is problematic in a whole different predatory way, as is everywhere, but we’ll get to those later). With left brain thinking, the rationale of the sexism is best summed up with the infamous Google memo, where a person saw attempts to fix the lack of diversity within the company as a threat and didn’t realize his response basically amounted to: “here let me logically explain to you why women are bad being emotionless AND bad at tech.” Seriously, if you’ve never actually read the memo, it is way worse than you think. And, of course, it’s filled with all these logical approximations and givens which give this toxicity the air of “intelligence.” But also-of-course, this habit is not limited to tech. In the larger film discussion, I see a bunch of people talk about female filmmaking and not realize they sound exactly like Google Memo Dude (or worse, they may even want to sound like him).

The problem with engaging the subject of logic is that it tends to elicit a knee-jerk response from those who worship logic. For any attempts to curtail such worship are often met with the assumption that we are saying “logic is bad” (which is absurd, or dare I say illogical). Because of course logic is fucking important. It’s intrinsic to our daily thought. There is literally nothing coherent in our minds without it. Not even this sentence. The clear problem is with those who go to the extreme end of the spectrum. Because then logic becomes the armor of those who do not actually understand their emotions. More importantly, the do not see the way their emotions are currently effecting them. You read the google memo and it’s not hard to see how much of is loaded with fear and disdain. Why is that when he insists the opposite is true? Because every human being is an emotional being. To the point that our emotional intentions are often nakedly obvious. And it is especially true when we cannot connect and process our emotions, for they still guide and orchestrate our behaviors in ways we cannot understand (which is exactly why therapy and emotional growth are so critical). And to bring it all back to story absorption, if you go down the left-brain rabbit hole of film-watching, you are probably not seeing the way the film is emotionally working on you. And if you’re not seeing that, then you’re not seeing what’s really going on with your reaction at all. Which means you will not only miss the ways you’re not being logical, you will probably end up emotionally hurting someone else in the process.

And big surprise, this all comes out in our discussion of female filmmakers.

Which brings us to an article I read last week by Lili Loofbourow called “The Male Glance.” It is, quite simply, stellar. A perfect articulation of the ways that men will only give female art a cursory glance, make assumptions, and will be altogether blind to “female intentionality.” It characterizes so many incredible things about the ways that men don’t recognize when women are making jokes, along with the ways we “other” women and refuse to connect with them in the same self-examination that we do with male characters. But one of the things that struck me deeply about the article was the discussion of the toxic dialogue around Elizabeth Gilbert’s Eat, Pray, Love which just so happens to be the subject of the first essay of “criticism” I wrote under this persona. Looking back, what I wrote is fucking garbage. Really. It’s not only full of sexism-in-the-name-of-being-anti-sexist, it’s also so judgmental of a complex adulthood I didn’t even understand yet. The lesson of which is not to look back and go: “oh my, how far I’ve come!” Nor is it simply to own the ways you mess up. It’s to realize that this is a constant process, even now, and especially going forward. For the article still directly calls out a vast number of ways I look across the spectrum of art and still “glance” at it. And so the only response is to constantly listen, and learn, and undo the self in awe of understanding the subject before you.

Not-so-coincidentally, this is what I try to do every time I watch a movie. Put simply, I try to abandon preconceived notions. Not just in terms of watching trailers, but assuming X about filmmaker Y. Because every time I’m trying to “learn the movie,” I’m trying to understand what it’s after. I am trying to understand how it’s after it. For the movie itself is worth infinitely more than myself. It takes infinitely more thought to make the film then it does for me to go to a theater, watch it, and write something catty. No, the job of criticism is to meet it. To reflect it. And to never once look down on it. And then the job is to help you diagnose how you felt watching it and why. And when I am going to take a piece of art to task? Especially on morality? Especially when it might feed into my own prejudices like it did with Gilbert’s work? It cannot just be a logical glance. I am going to be damn sure I do my homework, work out the argument, and play fair… Because it all feeds into the nexus of not just filmmaking but our preconceptions about gender.

Especially our own.

2. Lady Bird & Nancy

Within criticism, I spend a lot of time talking about film and story craft. I do this because I love it. I do this because it is the particular altar that I worship at. I believe that understanding story craft helps a story transcend boundaries. I believe it helps make an audience member feel a thing in a way they might not have otherwise. It believe it elevates thematic messaging. The craft of story is everything I have committed myself to, studied, and care about. To put it simply, it is my life’s work and focus. But that makes sense because it’s also a complex, evolving thing with a lot of nuance. That should be obvious when looking at at the end of the year awards season, and we see all the ways some people subconsciously understand the effect of craft and yet cannot recognize the coherence and tact of certain craft choices, even when they are right in front of them.

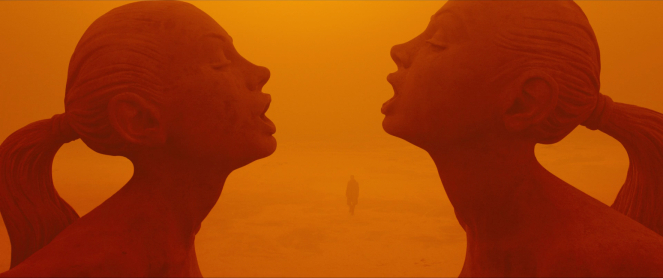

For instance, I bring up the old adage every Oscar season that it’s not “best” it’s “most.” It’s most editing, most costume design, most sound design, etc. What we’re really talking about is tangible details that we can latch onto and signify something clear to us. And since people assume they need ways of measuring if they are going to pick one over the other to give an award, they subconsciously gravitate toward “most.” So it’s easy to look at Phantom Thread and go, “my word, the costumes!” Just as it’s easy to look at the cinematography of something like Blade Runner 2049, with it’s immaculate, pristine framing of otherworldly production design and find it super impressive (and within Oscar voting, the fact that’s it’s shot by Roger Deakins, a white guy who is both a real-deal legend and has never won an Oscar before, certainly helps). But yeah, the real thing about Blade Runner 2049‘s cinematography is that it is tangibly impressive. But equally impressive in terms of cinematography, editing, and construction?

Greta Gerwig’s Lady Bird.

It just happens to err on the side of naturalism, which makes sense given that it’s a realistic coming of age story about a high school senior trying to find her place in the world. Thus, it is trying to echo that realism and make us feel a sense of intimacy with it. It needs to feel like life, not a “movie movie.” But there is no less craft in achieving that. Believe me, naturalism is insanely difficult to achieve. Quoting Daniel Day Lewis: “There is nothing more beautiful in all the arts than something that appears simple. And if you try to do any goddamn thing in your life, you know how impossible it is to achieve that effortless simplicity.” And we’ve all seen films that mistake “naturalism” for “what is the easiest / most natural to do on set” which is just put a camera on someone’s shoulder and film the actors haphazardly as they move in space. And not only is “docu-like” often lazy (and equally hard to do well), it’s counterproductive because it actually puts up another distracting layer away from your characters where the audience sees the movement and just feels the tonal unease. In fact, it often wholly eschews the point of cinematic language in favor of just draping one ongoing “tone.” But remember cinema is a language that is just meant to help you tell your story at every single moment. And Lady Bird takes up this charge of naturalism-yet-communicating-with-cinema and it fucking shines.

Yet as much as I talk about this, people still think I’m simply being generous to the film (which is some glance-y bullshit). So I’m going to go dive into a bunch of examples of how great it is. Of how the camera placement is endlessly intentional and communicative, especially when you look at it in terms of one of my favorite modus operandis which is: “face within space.” To wit:

I get this shot might seem like an obligatory two shot, but it’s just a really good example “Function 101.” Especially because everything about their blocking in this sequence is dead on. They both look in opposite directions, they’re clearly trying to get away from each other, their bodies on the edge of the frame, but they’re both trapped in this metal moving box together (which makes Lady Bird’s upcoming escape all the more funny). What makes the shot smart is that the thing that takes up the most space in the shot is the space between them. Pure character commentary.

Here’s something a little more noticeable. Ladybird, now smitten with her first love and getting swept off to a family party that just so happens to take place in the perfect house she’s always dreamt of. First off, it’s a good functional 3/4 shot (which is hard to do), but the intent is so clear: framing them ideally with the house behind them as they hold flowers and hands in her little American dream. But it’s not too overt. Meaning the shot not locked off or using single point perspective. It’s not creepy or overly composed. You just notice those details, while the most important human subjects remain the focus. They still feel realistic within the space while the rest of the space within the shot still 100% communicating the additional idea / intended emotion that it wants.

Here’s a another great 3/4 shot (the movie is full of lots of them). We get the out of focus suburbia behind, their drab school uniforms, but notice how much I’m talking about the actor’s blocking within these shots. It’s crucial here because the aim of the shot is to show their slumped shoulders and arms draped forward, all as they approach school with disdain and boredom. It communicates the feeling of mundane daily dread perfectly.

I love this shot. It’s not just the glow of the warm, soft light on their faces, it’s all the perfect subject emphasis of “face within space.” Lady Bird looks with adoration at her new crush on stage, all as her friend Julia has been relegated to the bottom of the frame, almost out of the picture. A complete foreshadowing to what’s going to happen in their relationship as she keeps her eyes on her new crush. But again, it doesn’t pan in or do anything too obvious. It doesn’t want you to notice the filmmaking. It says it all within the language of naturalism.

I love this one too. Again, she’s looking at her new crush subject with adoration, but this time she’s looking down on him. Which fits the way way she is effectively lowering herself in the conversation and feigning interest in his pretentious conversation, just as he doesn’t “raise himself” to her level. And then there’s the obvious communication of her chest being eye-level with him. Ha.

Another great shot. Not just texturally in terms of the soft lighting from the closed blinds, nor even the blocking of how she looks away from him as he pierces her with a sneer. It’s that it literally communicates the entire emotion of the scene and what is happening between the two characters. Both in terms of his callousness and her smoldering rage at how little he cares( and yet shrinking herself down to the corner). And at the same time, he’s putting himself selfishly at the center of everything. So, he is literally at the center of the frame.

And there’s even a great little blink and you’ll miss it moment in this scene. No it’s not the great detail of her tag sticking out the front of the dress. It’s in the emotional language of the two-shot composition where we understand what’s under their feelings, even though the two characters are at each other’s throats. This moment is showing what they’re actually saying underneath that. Because if you look at this shot and just see their body language? It looks like comforting and commiseration and crossing the line between them. It’s a perfect expression of what’s under their incredibly complex relationship. Notice how all these shots are the perfect expression of naturalism: it doesn’t want the care of the overt placement of the camera language to be what you notice. It wants the emotion of the actor to be front and center, and for the camera placement to simply help articulate their relationships. Their “faces with space.”

The alternative?

Guess what Blade Runner 2049 is communicating about a sexually rampant culture here along with our tiny place within it? The truth is people eat this stuff because 1) it’s glaringly clear and 2) it’s hard to construct on a pure production level. You need a bunch of money, massive props, rigorous camera testing, finding hues, and ultimately you are producing something that screams “Looooook at this framing!” Which is fine when you want to put a austere sense of distance between viewer and this film (and also be willing to suffer the setbacks of doing so). But it is no “better” than naturalism on any level (and in certain ways it’s easier). But note the symbolism of what is being communicated here is no more or less important than what is communicated with the subjects in Lady Bird (and in my argumentation, it adds up to something more coherent, too). Especially when you compare the “simple” language of the first scene of her in the car and then look at this shot from near the end…

Now in the car, the whole family sending her off to college, all looking toward the sun in same direction this time, all glaring soberly at the morning light of the new day. Each of the expressions telling a whole story of how they feel about this threshold moment: Lady Bird’s head up, eager to start. The mom, trepidatious, concerned. And the father, solemn, but unblinking and accepting. It’s everything they are in that moment.

And I can ask of nothing more from cinematography.

Which is only part of why Ladybird is an incredible film. I haven’t even mentioned how it’s best use of technical craft (outside of coming together for airtight story construction) is the editing. Every jump cut plays perfectly. Every scene ends right on beat and throws us into understanding the next scene by following her emotional arc. It’s all part of how we are so able to so richly go into the mind of a young girl who is both enthralled and terrified by the adult world that lays before her. It’s in how she idolizes the posturing ideas of what it means to be a cool adult. But it’s also in how she silently cannot grapple with the terrifying reality of the depression of the adults around her (the film would not bring it up twice, both with her drama teacher and her father, if it were not so important to understand what’s ahead of her). And it’s a film that understands the way they can come together in brutal nexus of teenager’s lack of sensitivity (the scene where you subtly reveal Tracy Letts playing solitaire in the background of their argument is just incredible). This is truly great stuff and should be recognized as so. And if you will allow me to be blunt, when I talk to DPs, they recognize this stuff instantly because it is the language of their occupation. And when you, as armchair movie opinion haver, cast aside films like Lady Bird as being not all that special in comparison to the overt language of the Blade Runners of the world, you may think you are innocently articulating what is a clear difference to you, but really you are just showing off your own ignorance.

Because this is all intentional.

And more importantly, everyone actually gets the effect of the incredible work in Lady Bird quite clearly. There’s a reason Gerwig’s debut had the highest Rotten Tomatoes highest critic score. It’s because it fucking works. And it makes deep, impactful statements that resonated with so many people in the audience. But we’ll miss the craft that got people there because it’s natural and “seems simple.” And so, the hilarious dance of only recognizing “most” goes on. And it’s why we will continue to fail to recognize the incredible craft behind the recent masterpieces of naturalism like Margaret, Once, Call Me By Your Name, Sing Street, Toni Erdman, 20th Century Women, Carol, Brooklyn, Short Term 12, Frances Ha, A Separation, Win Win, Winters Bone, and literally the entire oeuvre of Mike Leigh (who I think might be the greatest filmmaker alive). We don’t see the craft of these films when compared to those who shove it in front of our eyes in a glaring way.

And we double don’t see it when women are at the helm.

Even in the examples above, note how many of them are female-focused, emotionally focused, about complex two-hander relationships, or about LGBT subject matter. And when it comes time to actually talk about the craft in a lot of indie films we’ll throw facts like “it was shot on an iphone!” and it’s like “Fuck do I care? You wouldn’t even know what to do with an Arri 65 if you had one.” I just care about the quality of the choices. And we’re so badly missing the films that know how to uphold the basics of cinematic language. But with Ladybird, Greta Gerwig and Sam Levy nail it in such a perfect way (and before you just give him all the credit, this film is actually shot better than his Baumbach films, so freaking credit her too for pete’s sake. She’s the damn director). And when I look at it, it actually reminded me of one of my favorite films that uses the “face within space” approach brilliantly…

Alex Cox! But wait, who shot this film? Yup. A young Roger Deakins. And to that point, it doesn’t matter what the canvas you use, the paints, or the budget, there’s those who know how to use the ABC’s of the craft of cinematic language and those who try to fake their way through it. And Ladybird knows it’s fucking ABCs.

So there! I made the big argument that craft matters! Especially in the kinds of naturalist films where such craft is invisible! So I MUST be arguing that if all films did this, then we’d have a plethora of female-directed films that are worthy of acknowledgement! Or I MUST be arguing that these kinds of films shouldn’t go home empty handed! Well, no that’s not really the point I’m after here… Because I’m going to tell you a dirty little secret… My life’s work? The altar I worship at? Everything I care about?

It’s not that important.

3. Wrinkles

I have not seen Ava Duvernay’s Wrinkle In Time yet, but it’s one of my favorite children’s books (and comic, if you’ve never read Hope Larson’s adaptation) and I plan to see it soon. But I actually think the following argument works better if I haven’t seen it and can just make some observations about the dialogue surrounding the film. Why is that?

Because there’s a lot of white film bros who hate Ava Duvernay.

Did you know this? Boy howdy do they hate on Ava. And they won’t stop popping up in my damn feed (and always creating new accounts! Which is always a sign of being a well-balanced individual) to make “logical” points about how everyone’s just treating her nice because we surely must be afraid of backlash! And by not tearing her apart and by “pulling punches,” we must be doing this because we’re afraid to upset the critical status quo and call the movie bad, etc… I’m not kidding. I’m getting this all the fucking time. But it goes beyond the insidious than the overt RT score bombing for Black Panther and with Wrinkle it brings us to the obvious intersection with sexism. Which not strikes at the nonsense of gatekeeper thinking, but everything becomes this noxious up-is-down thinking as they try again and again make her prove why she belongs. They use her public relations background and the fact that she’s a strong promoter against her to explain why she’s not a real filmmaker. And yeah, it sooooooo reeks of Google memo thinking to be sure.

But let’s do a thought experiment. Pretend this doesn’t have to do with race and their fragile inner emotions (spoiler: it does. I mean, it wouldn’t literally bother them so much if it didn’t), and instead a gatekeeper-y conversation about how important “craft” is when it comes to the public discussion of films. See, a lot of people do not seem to know what to do with the simple fact that Wrinkle In Time is getting mixed reviews. Again, I have not seen it, I may adore it, I may dislike it, but having talked to a wide swath of people at this point, the arguments are with elements of the story craft, narrative propulsion, tonal control, and things I am quick to identify and talk about in these columns. Because yup, these are important things in direction, especially in big popcorn filmmaking. And talk about them I probably would. But since I have seen Duvernay’s last two films, that means I know some other things, too. I know that The 13th is as explosive, propulsive, and soul-rupturing an experience as you can have with a documentary. And I know that if I dig into Selma, sure, I might be able to pick apart a story choice here or there, but I was likewise blown away by the a litany of other choices that handle the complexity of its subject matter beautifully. Put simply, Ava’s greatest strength as a filmmaker is that she understands the power of her subject matter. She understands what to say about that subject matter and how to focus appropriately on that. And most of all, she understands the power that subject matter has on an audience.

Which brings us to the next obvious question: how important is “craft” in comparison? After all, I just made all these ongoing arguments about how it transcends boundaries, but it can be hard especially when people can’t see how good a film like Lady Bird really is… But either way it brings us to the cold hard truth…

You transcend more boundaries through subject matter than craft.

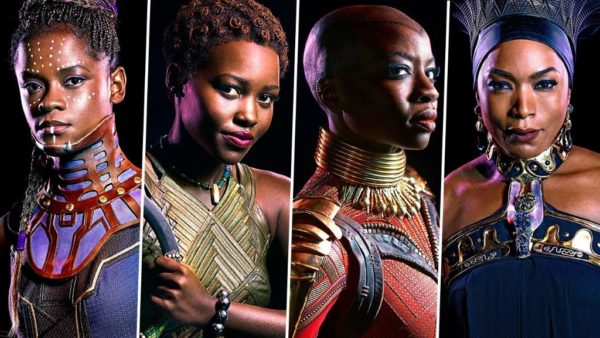

Because of course you fucking do. Subject is, and has always been, the anchor for the vast majority of filmgoers. To wit, it’s the reason Black Panther was a damn event. The clamoring of an entire population of Americans who had been waiting for Hollywood to “get around to this” for decades. As white people, we barely notice this because we have a litany of personal choices before us, but it’s almost always why we see a certain movie in the first place. Even with Blade Runner 2049, why did a lot of guys adore it? Because for as much lip service as it gives other issues of identity, the film uses overt stylistic filmmaking conventions to tap directly into traditional masculine posturing and lone wolf independence, while simultaneously getting to just the “right amount” of unspoken sentimentality, all while “poetically exploring” a bunch of very hot women getting naked and getting used as props. Which all means Google memo dude probably would have loved it. But hey, I can name a million popular dude movies like that. It’s subject matter that, however we dress up with craft, we can always fall into indulgently. Likewise, we have to account for the bevy of female critical reactions to Blade Runner 2049 who recognized the craft, but were so off-put by the film’s handling of their subject. Even today, I spoke with a casual movie-goer that said watching it “felt humiliating.” This stuff is real. And it’s what happens at the nexus of ignoring subject and effect of these films.

For example, I look at the subject of Phantom Thread, which I argue again and again is a horror movie in the vein of There Will Be Blood, where we are meant to watch in terror as these two fall into a toxic co-dependent relationship. I think the film is absolutely aware of this. I think it plays the beauty of the romance ironically (the same way all Paul Thomas Anderson’s later work has). I think it’s a masterpiece that inspires self examination (like all the times I didn’t want to get in an argument because I had an important meeting or some shit and then I see that on screen and realize “Holy fuck, I was being so callous.”). But I also see so many dudes shake their head and be like “oh, it’s just what relationships are like, isn’t it funny?” while I’ve had endless women say things akin to “watching it was erupting the PTSD of my worst relationships.” … The subject just matters.

Which is what we have to recognize (and not dismiss as “less than”) when we talk about Ava Duvernay, because her mission of subject matter is truly more important than whatever you might make of the execution. I immediately think of Tessa Thompson’s comment, “For days after seeing #AWrinkleInTime I thought about how powerful it was to see a biracial character in a big studio movie. @ava beautifully normalized what so many families look like. I wish my younger self could have seen this. That she could have been seen like this.” and @AlannaBennett chimed in, “I maintain that if my younger self had seen it it would have been a game changer.” And now, I have a very important and blunt message to anyone who doubts the veracity and power of these statements:

Fuck off.

Seriously. For it would take the least gracious among us not to listen to someone telling you how meaningful something is to them. To tell you what it’s like to always look up on a screen and never see yourself. Especially if that truth is one you can never know, or understand, because you’ve never had to do it. Because you’ve never been rendered invisible in your own culture. Being able to ignore that would take having an omnipresence of cultural riches so innate to your own experience, that the sheer idea of “not understanding what it feels like to be unrepresented” would be completely foreign to you. Because you always see yourself. Everywhere. And thus, you have no damn idea how important a movie could be for the 12 year old girls who don’t get to see themselves. Who don’t get to see themselves be interested in STEM, or get to be the travelers through the universe. And so for the most callous thinkers who still come to accept this, it brings up an equally-callous question…

“So is it as simple as putting women / POC in leads they are often not afforded? And giving women / POC the opportunities to tell those stories?”

Well, when that hasn’t happened before? Fuck yes it is. Because as much as I worship at the altar of craft, the subjects will always matter so much more. And we must strive to enrich the breadth of our cultural landscape and subject matter with the same exact fervor that we strive to enrich our understanding of cinematic craft. For they are one in the same. But the reason we do not equate these two, nor strive to embrace this progression is simple…

There’s a lot of people not ready to let go.

4. The Dying Cowboy

Before I get into it, I want to be clear: Wind River is an incredibly well-made movie.

It’s taut, harrowing, and gorgeously shot. It alternates between ponderous expanse and kinetic energy with rapturous glee. Both Renner and Olsen give stoic, heartbreaking, and sensitive performances. Heck, the film even knows how to use a real-deal story-purpose-laden flashback. And in terms of subject matter, Wind River is often quite respectful of the Native American culture it portrays, whether in terms of the pride, plight, or harrowing realities they face. It’s also the kind of great, self-contained revenge movie people aren’t making all that much any more (at least not above the micro-budget level). But as much as I enjoyed the craft of the film, it couldn’t help but raise a lot of questions in me about the future of these kinds of movies. And it’s starts with one simple fact:

It is a movie about the victimization of Native American culture.

And it is starring two white leads taking up that charge.

Again, there is nothing about their portrayal that is surface-level offensive. This isn’t a Last Samurai scenario and Jeremy Renner does not dress as a Native American, nor does he try to be “the best” at Native American things. In fact, the film shows constant awareness of the ways he should not try to usurp their culture, just understand and show deference to it. He understands the differences between them. He understands he is a cowboy and that he simply married into this world and respects it. In most other portrayals of the past, it would ostensibly be about the white indulgence of “going native” a la Dances With Wolves or something, but Wind River knows enough to avoid those pitfalls and at least say the right things. The problem is, still, the issue of identity and subject. Because this is not a movie about being an outsider coming into a culture. This is a cultural revenge movie. Which just means that under the lip service and deference, this is still the kind of movie where the white character carries the weight of that revenge, and the Native American characters become props for that revenge. This is the simple reality of subject. Which brings me to the core question.

Why isn’t Gil Birmingham the star of this?

He’s an incredible actor. He’s probably the most popular Native American actor working today. And his performance as the aggrieved father in Wind River and his haunting final scene is pretty much the first thing anyone talks about. He’s even been in blockbuster films before, so you can give me all the lectures you want about which actors move the needle, but I work in this fucking industry. I know it’s all bullshit based on false associations and prognostications of international playability that have already changed. Besides, we are now living in the post-Moonlight world where that film makes 25 million more than films like Wind River. Identity and subject matter is what matters to an increasingly diverse audience that wants diverse films. And yet, we see the idea of our biggest Native American star starring in a Native American revenge movie as an impossibility. And the results are telling, as Gil apparently wanted to take Graham Greene’s role because it had more screen-time (oof). But if we cant let Native Americans star in their own god damn stories, how can they ever get someone in the position to be a star in the first place?

The ugly truth stares us in the face: we want to use Native Americanism for our own purpose. It’s really not unlike the core messaging of Get Out. We will use them as props and things that make us better, before we see them as their whole selves with a right to the same kind of whole personhood as ourselves. Which all just highlights the obvious: that as much as has changed with a diverse audience, it’s still a Hollywood where Wes Studi gets to give a speech at the Oscars, but he still got more diverse roles in the late 90’s then he does now… and we have to keep clamoring that we don’t want this to happen.

We want the subject to be the subject.

So when does inherent-white-lead-ism finally die? Well, it will happen when Hollywood finally stops making excuses, finds some courage, and trusts when people say they want what they want (but we’ll get to more of this in a second). But for now, while we’re talking about Wind River I want to talk about its intersection with the politics of gender, wherein the film more reveals its not-so-subtle conservative streak. Because, make no mistake, this film is about protecting the sexuality of beautiful young Native women. Renner even delivers a line about not letting your guard down for one second (because then your beautiful daughter will get raped and die). And yes, there are enough signifiers within the film to give the daughter a life and soul beyond that notion. But, in the end, the film expressly states that her value as a person, and especially as a woman, is in how far she ran in the freezing cold to get away from her rapists. That is what gives her value. And it never asks or even contemplates the other courage to survive the ordeal by not running. But of course that would never factor in, because that result is still the worst thought to the conservative male mind (cue the litany of dad’s who never understand why their daughters would “stop fighting” sexual assault at a certain point and the shame that come with it). Let’s not pretend this is anything new. These kinds of rape-purity stories have been around in Hollywood forever precisely because they dive deep into the fears of the conservative male mind (and I use that word conservative because that’s exactly what it, no matter how many liberal thinkers are guilty of the same thinking. So you have to call a duck a duck). And this fixation reveals yet another deeper, uglier thing… It is fascinated by the same sexuality it seeks to protect.

There’s even a shot choice that tells us everything about it.

During the autopsy scene of Wind River, the daughter lies dead, naked on a slab, having just been autopsied. Revenge movies love these kinds of scenes. They’re seen as motivational. The actual screenwriting term for the motivation that comes out of a dead loved one is actually “fridge stuffing” and so autopsy scenes supposedly ram home the death and carnage. And yet, there’s also a lot of highly sexualized death imagery in these scenes and the problems with them have been talked about endlessly (simply put, it’s exactly what some men want). At first, Wind River seems aware of this. You can see a bit of her body just out of the bottom of the frame. You see her face, some edge of gore of the open cavity. But it cuts around her as the characters point things out and mostly argue about cause of death. But then it cuts to a shot of her hand… and there on the far, far left side of the frame, and only slightly and cut-off… is her vagina. Make no mistake: this is an overt choice. You do not frame a shot like this by accident. And so my immediate thought for the filmmaker, which I will put as bluntly as possible was this: “do want to show me her dead vagina or not?”

I say it bluntly because the subject matter is: blunt. There is no tasteful way to show me the dead vagina of the young girl whose sexuality you were so keen to protect in this film. And trying to ascribe a tasteful shot over it, means you understand the problematic nature of that which you are actually showing me, and instead of owning that, you are trying to skirt around it while still doing it. And I can’t tell you how many dead bodies of women we’ve seen shot “tastefully” and still fail to recognize the inherent duplicitous problems that come with it. As an obvious counterpoint, the reason the autopsy scene in Silence of the Lambs works so damn well is because it’s actually fucking terrifying. Not just in the build-up and the characters reacting to the noxious smell, but the way it even deals with the character arcs of them facing their fears. There’s a point to it. And there’s nothing sexualized to the scene it all. Every bit of it is directed toward the sensation of the audience’s fear. The scene works because the way they shoot it ACTUALLY IS scary and horrifying.

So you can tell me all you want that your autopsy scene is supposed to be raw or scary, but if you just want to dabble with your “tasteful” naked girl on a slab, you’re trying to have it both ways. Which actually brings us full circle right back to the male glance. Lili writes: “The male glance is the opposite of the male gaze. Rather than linger lovingly on the parts it wants most to penetrate, it looks, assumes, and moves on. It is, above all else, quick.” Note the way her description for both of the terms is 100% characteristic of the way this scene is shot. Meaning it is both the glance and the gaze. And it is this way for much of the movie, which brings us to the constant contradiction of Wind River, whether camera work, sexuality, or even race: it is trying to have it both ways.

Which really means you’re just trying to have it all.

And so for this story about beautiful Native American women being abused and lost, it doesn’t matter how much the reality of that final title card stings. Because it doesn’t matter if Native American Women are the only group of missing people who are not kept track of when story doesn’t honor the personhood of what is lost and instead helplessly falls into the glaring contradictions of whether their sexuality is protected and whether or not we admire their moxie. Sure, it cares about Native American women, but not enough for it to ever be their story. And in the thematic world of subjects and meaning, the harsh reality is actually the equivalent of even the Google memo… A movie that is not talking about what it’s really talking about.

And that’s the real reason why the mythical “Cowboy” trope is dying: the rest of the world is tired of being the side character in their own stories. When they’re tired of being the prop, the subject of glance and gaze, then there is no one left for the cowboy to save. But the truth is the Cowboy has always been romanticized, just as he’s always been dying. After all, it’s the reason we say all great westerns are “about the end of things.” For it just gets at the white male instinct to converse, to hold onto, to protect, and the inability to reckon with a world which is changing. Sometimes they let go. Sometimes they fade away… And sometimes they hold on for dear life until they become the bad guy for that very act of trying to hold on. And that’s the rub, isn’t it? In order to include and evolve…

We have to give something up.

5. The Power Game

Allow me to take all this and finally get to the damn point…

This is all about power.

When it comes to filmmaking, I (and many white dudes like me) grew up dreaming of making movies. And the thing is, I was always told I could do this. My parents, who I am sure would have loved it if I stuck with practical STEM aims, always supported it. Hell, everyone in my town knew I wanted to work in the movies. They would celebrate this. They would tell me “invite me to your premieres!” Even all my non-STEM teachers supported it. Everyone told me I could do it. And in the end, they did this because I fit the proverbial mold. I did good in school. I followed movies with passion and fervor. I was a precocious little scamp. And I was a white dude. So I took this path because there was no reason I believed I couldn’t. I didn’t come from money. I knew it would be hard. But it was still what I was “supposed to” do. And so I, and many white dudes just like me, pursued it.

But, of course, the path of getting into entertainment is insanely competitive. All us white dudes show up to the same place for the same limited jobs and paths. And getting through it takes all kinds of luck. It takes working insanely hard. It takes constant courage. It takes pressing through self-doubt. It takes endless failure. And I don’t say this to imply I’ve succeeded in these things. I will readily admit all the times I turtled. And more troubling, all the the times I outright manipulated out of fear and cowardice, all in an effort to keep pursuing what I wanted. Which is beyond shitty and something you have to learn to never, ever do. But ultimately, I’ve just tried to do my best, own my worst, and keep surviving and doing even better. But the troubling thing about this whole path should be obvious…

This kind of experience is what breeds conservatism.

When you grow up believing you have a proverbial “spot,” even if you have to work your ass off for it, it breeds fear you will not get your spot. And it breeds fear you will lose your spot once you have it. It breeds the fear you might not be destined for the thing you were told (and believed) you could do your whole life. It breeds jealousy. It breeds resentment of those who you believe do not get their spot “for the right reasons.” Especially because they’re not as smart or good as you. And to be clear, that’s all fucking garbage. Not only are there no “spots” in this way, it’s completely wrong way to open and close your brain up. Because you actually do want to be myopic in the sense that you don’t worry what’s going on with others, there is only your path. There is only working hard and trying to do right. You can’t worry about the other person. And when you do look externally? You want to realize you work in an industry built around a communal, collaborative art form. It is an industry where “a rising tide lifts all boats” and you can help one another. Thus, to be fearful and think in terms of “conservation,” really only hurts you.

And most of all, you cannot imagine how much harder it’s been for people who haven’t been told “they can do it” all their lives.

It is so much more difficult for those who don’t fit the white dude movie lover mold. It’s downright systematic. You have to watch as female filmmakers from your classes slowly get railroaded into being producers, editors, and working in public relations instead or storytellers, all because “thats where they fit.” Just as you have no idea what it’s like to be a minority and get constantly used as a prop of collaboration and not get to be the engine of it. So you have to understand that something that has been so hard for you, has actually been 1000% harder for someone else. And sure, you can be sensitive to that idea all your want. You can say it’s unjust. You can say you want more female and minority filmmakers. But when you put forth the perfectly-sane and not -radical idea that “50% of studio films should be directed by women and 40% should be directed by minorities,” people lose their god damn minds.

Seriously. I’ve been having this exact conversation for, like, a fucking decade. Sometimes with insanely talented and amazing people. But they all fear it because they assume it automatically means they wont get to make their movie (never mind the kind of fear they would experience if people like them were only allowed to be 7% of directors). And I’ve had so many loving, kind supportive geniuses tell me that quotas just don’t belong in the arts (which is exactly how 88% of directors end up being white males). But it’s all because of the deep, conservative fear: they don’t want to give it up available “spots.” Which means the dark truth is that no one wants to give up on a world where movies look like Wind River because no one wants to give up their place in the center of the story because it means giving up your place as the center of the universe. And out of this deep fear, we subconsciously create a system of rules that breed forgiveness and leniency for ourselves, while we subconsciously punish what we fear… But the results of this aren’t subconscious at all.

It actually creates the “controlling double standard.”

It’s a constant facet of intersectionality and society. For example, when you look at institutional prison bias, “@CateDelia wrote beautifully, “whites shifted burden of proof to women smoking crack to prove their own humanness, but because their use of crack ‘showed these women were animals’ in white folks’ eyes, for the ‘safety and continued contentment’ of the 1980s’ white coke user, black women were caged for life…” It’s a devastating systematic reality. By the way, I’m not floating back and forth between discussions of race and sexism to directly equate them, nor would ever do that. The whole point of intersectionality is to understand the similarities and especially the differences. And if you constantly have to prove a black woman’s right to be an artist, while working on the assumption that the movie-loving-white-dude like me has an inherent right to it, then you control all the power of who gets to do it (along with what subjects are chose). There’s a reason all these conversations about Ava Duvernay become so toxic. And the result is a system where relative power is kept in check.

For instance, quick, name 5 black female filmmakers…

Off the top of my head? I shamefully only get to four. But this comes from a system where we can only see our own struggle, which really means we have the completely inability to recognize when we have everything. It’s a notion captured amazingly when @mrfeelswildride tweeted “This single worst sentence I’ve ever read” about the following statement: “Geeks should rejoice in Ready Player One. This is their Black Panther.” Which is flabbergasting for lots of reasons. The first is automatic implication of exclusion of black people from being part of the white geek circle. The second is the audacity to even make that fucking comparison. And the third is the laughable idea that white geeks haven’t been already been enjoying a bacchanalian indulgence of white geek movies for the last 18 years. And that merely letting Black Panther exist, inspires a thought of “now it’s our turn!” It’s like… what the fuck? But that’s what happens with selfish myopia. You go down the rabbit hole of wanting more, more, more for yourself.

Which is literally the non-ironic subject of Ready Player One.

Which brings it all together as a comparison point for the interesting way the conversation revolves around Steven Spielberg. To be clear: I think he’s the greatest living American filmmaker. I think his mastery of the craft and cinematic language is everything I hold dear. I could do endless cinematography classes just with his movies. There’s a reason he’s made countless masterpieces both in terms of high-brow and popcorn fare. But if you think that makes him bulletproof, or deserving of anything more than he’s already gotten, that’s not how it goes. For there’s a whole generation of people who really just don’t care about his subject matter. You have to realize he’s rarely has female leads. And his art about the minority experience might have been brave once upon a time, but the audience has evolved beyond it. Now, there’s a streak of dying cowboy-ism that comes in the form of the geek apocalypse porn that is Ready Player One, which is even downright self-referential. And there’s a reason that this subject rankles people beyond mere nostalgia. And it’s subject and inclusion. Which brings us back to the ongoing point.

I can argue about craft all I damn want, but if white men have the monopoly on what constitutes “good craft,” then craft is fucking worthless.

Because that discussion matters only in a perfectly fair system (and we’ve seen how fucked up and toxic Hollywood can be this year when it comes to male abuse). Even the discussion around it is messed up. I mean, I get to write these essays where I basically just piggyback and contextualize the thoughts of brilliant women and minorities and I get pats on the back for merely recognizing it and doing the bare minimum. Everyone else has to live it. And everyone in my position loves to believe they do the right things to fix that system, but that’s bullshit. I remember being in a situation where everyone wanted to do the right thing and hire a female director for a certain episode. We pursued endless options we loved that simply couldn’t do it, and kept getting an embarrassment of great male candidates. And when time came to vote, I had to choose between the safe genius of established talent vs. a unestablished female director who wanted to make tonal changes and I believed was fundamentally wrong for the episode. So I voted safe. I did it out of the belief this “had” to be good because of everything being risked, etc. It’s really just another kind of cowardice. But it’s also not even about the logic of the choice in that moment. Because there’s a whole system that led to that moment and the perceived “lack of options,” and it’s the same one that leads to a world where everyone wants to choose that perceived safety. And that’s how it stays 88% white male. Which means the onus has to be on the larger system that needs to be fixed. Both in terms of how we talk about that system and the policy we create.

To wit, we cannot get obsessed with being the arbitrators of which female filmmakers are good and which are bad. The only real truth is we need way more of them. We need ones that understand subjects. We need ones that are masters of craft. We need every kind of female filmmaker. And in turn, we need to get better at recognizing female intentionality and their craft. Just as we need to stop being so freaking lenient on white male filmmakers who don’t measure up in the same way. We need to be more vocal against people who see the mere presence of a lesbian character in the thing that they like as an “invasion of their space.” We need to stop being “logical” about all this. We need to stop Google Memo-ing this. So that means yes, we need to embrace a call for quota thinking industry wide. It goes beyond the inclusion rider. We need to agree that 50% of studio films should be directed by women and 40% by minorities (in short, stay in line with population, just like many other industries have to do to show fair hiring practice). We have been fucking this up and controlling it for too long. We need to agree that a range of subjects matter to a world made up of many more subjects.. We need to agree that people should get to direct their own stories about their own worlds. And we need to take it out of people’s hands and put it into the realm of systemic solution. Because it’s a truth so simple as to be forehead-slapping-ly simple:

It’s time to make movies look like the world they actually inhabit.

Fear it not.

❤ HULK